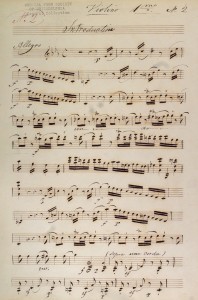

Are you a Beethoven or a Mozart? If you’ll pardon the familarity, are you more of a betty or more of a mozzy? I am a betty. I am not referring to my musical abilities but to my writing style; actually, not the style of my writings (I haven’t completed any choral fantasies yet) but the style of my writing process. Mozart is famous for impeccable manuscripts; he could be writing in a stagecoach bumping its way through the Black Forest, on the kitchen table in the miserable lodgings of his second, ill-fated Paris trip, or in the antechamber of Archbishop Colloredo — no matter: the score comes out immaculate, not reflecting any of the doubts, hesitations and remorse that torment mere mortals.

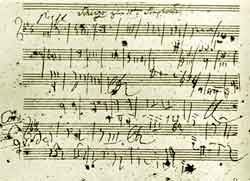

Beethoven’s music, note-perfect in its final form, came out of a very different process. Manuscripts show notes overwritten, lines struck out in rage, pages torn apart. He wrote and rewrote and gave up and tried again and despaired and came back until he got it the way it had to be.

How I sympathize! I seldom get things right the first time, and when I had to use a pen and paper I almost never could produce a clean result; there always was one last detail to change. As soon as I could, I got my hands on typewriters, which removed the effects of ugly handwriting, but did not solve the problem of second thoughts followed by third thoughts and many more. Only with computers did it become possible to work sensibly. Even with a primitive text editor, the ability to try out ideas then correct and correct and correct is a profound change of the creation process. Once you have become used to the electronic medium, using a pen and paper seems as awkard and insufferable as, for someone accustomed to driving a car, being forced to travel in an oxen cart.

This liberating effect, the ability to work on your creations as a sculptor kneading an infinitely malleable material, is one of the greatest contributions of computer technology. Here we are talking about text, but the effect is just as profound on other media, as any architect or graphic artist will testify.

The electronic medium does not just give us more convenience; it changes the nature of writing (or composing, or designing). With paper, for example, there is a great practical difference between introducing new material at the end of the existing text, which is easy, and inserting it at some unforeseen position, which is cumbersome and sometimes impossible. With computerized tools, it doesn’t matter. The change of medium changes the writing process and ultimately the writing: with paper the author ends up censoring himself to avoid practically painful revisions; with software tools, you work in whatever order suits you.

Technical texts, with their numbered sections and subsections, are another illustration of the change: with a text processor you do not need to come up with the full plan first, in an effort to avoid tedious renumbering later. You will use such a top-down scheme if it fits your natural way of working, but you can use any other one you like, and renumber the existing sections at the press of a key. And just think of the pain it must have been to produce an index in the old days: add a page (or, worse, a paragraph, since it moves the following ones in different ways) and you would have to recheck every single entry.

Recent Web tools have taken this evolution one step further, by letting several people revise a text collaboratively and concurrently (and, thanks to the marvels of longest-common-subsequence algorithms and the resulting diff tools, retreat to an earlier version if in our enthusiasm to change our design we messed it up) . Wikis and Google Docs are the most impressive examples of these new techniques for collective revision.

Whether used by a single writer or in a collaborative development, computer tools have changed the very process of creation by freeing us from the tyranny of physical media and driving to zero the logistic cost of one or a million changes of mind. For the betties among us, not blessed with an inborn ability to start at A, smoothly continue step by step, and end at Z, this is a life-changer. We can start where we like, continue where we like, and cover up our mistakes when we discover them. It does not matter how messy the process is, how many virtual pages we tore away, how much scribbling it took to bring a paragraph to a state that we like: to the rest of the world, we can present a result as pristine as the manuscript of a Mozart concerto.

These advances are not appreciated enough; more importantly, we do not take take enough advantage of them. It is striking, for example, to see that blogs and other Web pages too often remain riddled with typos and easily repairable mistakes. This is undoubtedly because the power of computer technology tempts us to produce ever more documents and in the euphoria to neglect the old ones. But just as importantly that technology empowers us to go back and improve. The old schoolmaster’s advice — revise and revise again [1] — can no longer be dismissed as an invitation to fruitless perfectionism; it is right, it is fun to apply, and at long last it is feasible.

Reference

[1] “Vingt fois sur le métier remettez votre ouvrage” (Twenty times back to the loom shall you bring your design), Nicolas Boileau

While the the differences between the composing “workflows” are true in general, musicological research of the last two to three decades has proven, that this is actually not the full picture. Yes, Mozart tended to do much more of the design processes of composing inside his mind without visualizing it on paper and without long pauses between the different “design stages” of a piece, as we find it in Beethoven’s work. And yes, in Mozart’s work, we find much more fragments than sketches. If he felt, he cannot make progress as much as he wanted, he often preferred to leave a work unfinished and to start a new, different work from scratch.

BUT… there are Mozart sketches, which have been found only some decades ago, and these sketches change the picture of Mozart, that had been passed on since the Romantic era, the picture that claimed that he has been an absolutely perfect mind worker quite significantly. The reason for this change is that the sketches show that Mozart often had a hard time with relatively “simple” routine tasks. For example, many found sketches of pieces based on the sonata form (sonatas, string quartets, solo concertos, symphonies) deal with finding a good and persuading transition within the exposition between the first and the second theme. Basically, in practice, this is nothing more than a modulation (to the dominant key in movements in a major key and to the relattive major key in movements in a minor key) using motives from the already presented first theme or deriving some contrasting motives out of the thematic material that had been presented before. This is a routine tasks that requires more “crafting” than ingenious idea generation. Yet still, the found sketches of Mozart clearly show, that, curiously enough. he struggled especially with these routine tasks, trying out many, often very different, versions, before he found a solution that he proved a convincing.